I’m working on the first draft of my next book—an Appalachian young adult horror—and I’ve been doing a lot of research on a range of topics, from Blair Mountain to mountaintop removal to folk magic. One topic is kudzu, also known as the “vine that ate the South.” The magical yet invasive vine is a common sighting around my neck of the woods here in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, and it’s an important character of sorts in my current work in progress.

As part of my research, I read Devoured: The Extraordinary Story of Kudzu, the Vine That Ate the South by Ayurella Horn-Muller throughout January. (Reviews below!)

While I expected to learn more about this notorious vine, I also read about much more through the lens of this plant: white supremacy, state-sanctioned violence, and the history of and violent rhetoric on immigration in the United States.

This book is a testament that everything is political. Books are political. Hell, plants are political. It’s not about whether or not something is political. It’s about whether or not you’re going to engage with it.

The world needs us to engage. To keep engaging. I can’t do everything, you can’t do everything, but we all can do something.

If you need a place to start, pick up one of these nonfiction books and contact your representatives.

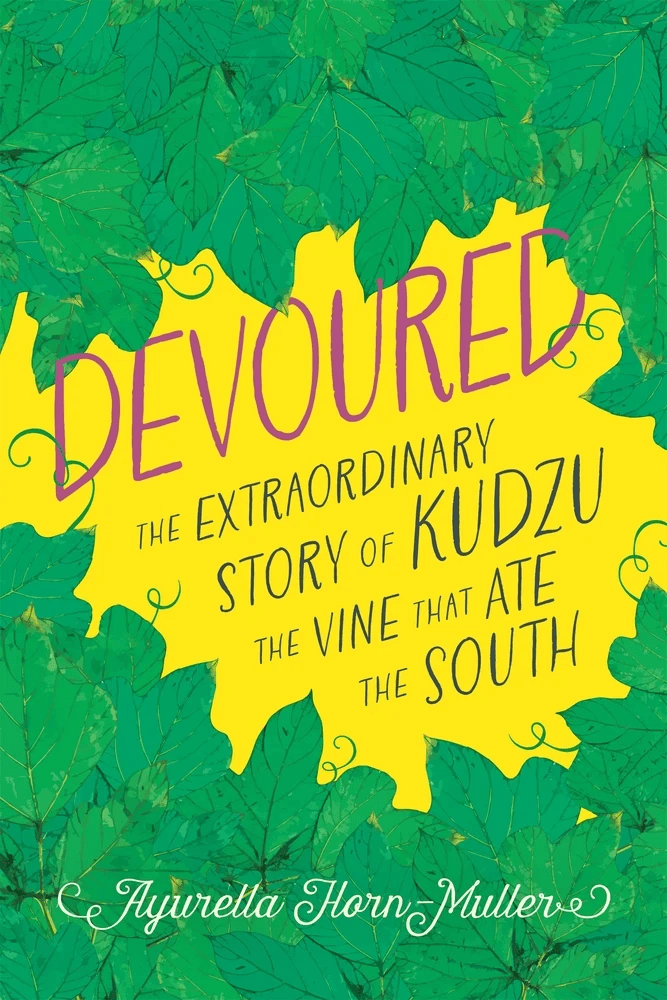

1. Devoured: The Extraordinary Story of Kudzu, the Vine That Ate the South

By Ayurella Horn-Muller

Kudzu abounds across the American South. Introduced in the United States in the 1800s as a solution for soil erosion, this invasive vine with Eastern Asian origins came to be known as a pernicious invader capable of smothering everything in its path. To many, the plant’s enduring legacy has been its villainous role as the “vine that ate the South.” But for a select few, it has begun to signify something else entirely. In its roots, a network of people scattered across the country see a chance at redemption–and an opportunity to rewrite a fragment of troubled history.

Devoured: The Extraordinary Story of Kudzu, the Vine That Ate the South detangles the complicated story of the South’s fickle relationship with kudzu, chronicling the ways the boundless weed has evolved over centuries, and dissecting what climate change could mean for its future across the United States. From architecture teams experimenting with it as a sustainable building material, to clinical applications treating binge-drinking, to chefs harvesting it as a wild edible, environmental journalist Ayurella Horn-Muller spotlights how kudzu’s notorious reputation in America is gradually being cast aside in favor of its promise.

Weaving careful research with personal stories, Horn-Muller investigates how kudzu morphed from a miraculous agricultural solution to the monstrous archetypal foe of the southern landscape. Devoured is a poignant narrative of belonging, racial ambiguity, outsiders and insiders, and the path from universal acceptance to undesirability. It is a deeply reported exploration of the landscapes that host the many species we fight to control. Above all, Devoured is an ode to the earth around us—a quest for meaning in today’s imperiled world.

Review:

★★★★

I picked up this book as personal research into kudzu—the magical vine that has engulfed large portions, especially along the highways and edges of the Blue Ridge Mountains, of my home in the Shenandoah Valley. I expected to read about the invasive weed’s history to and through the US, its environmental impact, and its variety of uses. I did read about those things, but I also read about much more.

As Horn-Muller, a second-generation American, summarizes in the introduction, this book examines how “kudzu morphed from a glorified, miraculous solution for soil erosion into a monstrous archetypal villain of the landscape[…]and how that contributed to cultural and racial dissonance for years to come.” In short, everything is political, including kudzu and the language we use regarding this plant.

For a little over a century, ‘alien invader’ has been used as a common phrase in entertainment, media coverage, legislation, and literature produced by state and federal agencies about kudzu. But this wording is not just used to describe a plant that most people want gone. For centuries, it has been exercised to signify people.

I didn’t expect for my interest in kudzu to lead me to the history of and violent rhetoric on immigration in the United States, but it did. In a time when our government is mobilizing ICE across the country and terrorizing our communities. Murdering its civilians. Denying our reality, even when documented, as it has time and time again.

Today, I found out that ICE is considering a new detention center in my small county. I fear the violence and cruelty this would bring to my immigrant family, friends, and neighbors, as well as the compounding hatred and ignorance this would perpetuate. I urge us all to continue to contact our representatives. Get involved in our communities and support mutual aid efforts. Make a bid on the Publishing for Minnesota auction. Read a book from a Minnesota Press. Take care of our loved ones. Visit our local libraries. Take action of all kind, on all scales. As kudzu teaches us, justice is intersectional, from environmental to racial justice. May our actions, big and small, of love and solitary compound towards a better world for all.

All too often, I have longed to shed my distinct ancestry; to be worthy of an American stamp of acceptance. Too many times, I have longed to remind those around me: ‘I am here because I have a right to be!’ So why did it feel like I was trespassing, as if I’d crossed some invisible line? It never made much sense to me how anyone from a country with an origin story like the United States could be so opposed to welcoming people with beginnings beyond these borders. Much like kudzu, the former pulsing heart of a green, southern kingdom, I felt as if I was diminished and criminalized by the very living descendants of communities that had once welcomed the arrival of those similar to me. It’s not hard to see parts of myself reflected in the stand of kudzu I stand before. First embraced, then shunned and eventually accepted with lasting disregard. Unable to escape the otherness that brands us—the ones from distant places. But still thriving, against all odds, labels, and unjust expectations.

But outside of schoolbooks and nursery rhymes, the reality of the world in which we live teaches us grim truths. Sometimes, the horrifying monsters that walk among us wear perfect, pleasing faces. Sometimes, the people we know best are also those capable of inflicting the most pain. Sometimes, the scariest things take place in the light of day; nightmares play out in visible places surrounded by people who decide to look away, where none are willing to stop explicit acts born from hate. Life teaches us these lessons, and some of us are forced to learn earlier than others. By nature of our circumstances, of the ancestries we’re born into, of the skins we cannot shed. We learn that people are often motivated by greed and a sense of glorified self-preservation. We learn that the space between good and bad is almost always blurred. And we learn that the things we end up fearing most are nothing like the vanquished creatures we once dreamed about. For the root of all of our problems is the fathomless part within ourselves. It is the human need to conquer and to control the narrative at any cost. These lessons can be applied to the origin stories of everything that we’ve shunned and cast aside. Like the seeds once planted that flourished into a seemingly invincible vine that would go on to inspire urban legends of the South.

My only critique of this book is that, while I mostly enjoyed how the chapters read like separate articles, the book sometimes felt disjointed, which resulted in some repetition and slower pacing.

Overall, Devoured offered insight into the world around me through the lens of a plant I regularly see in my home state. It also offered me courage to continue taking action. As Horn-Muller quotes, author Alice Walker wrote the following in a New York Times article in 1973: “In Mississippi (as in the rest of America) racism is like that local creeping kudzu vine that swallows whole forests and abandoned houses; if you don’t keep pulling up the roots it will grow back faster than you can destroy it.”

Immigrants make America great. Abolish ICE.

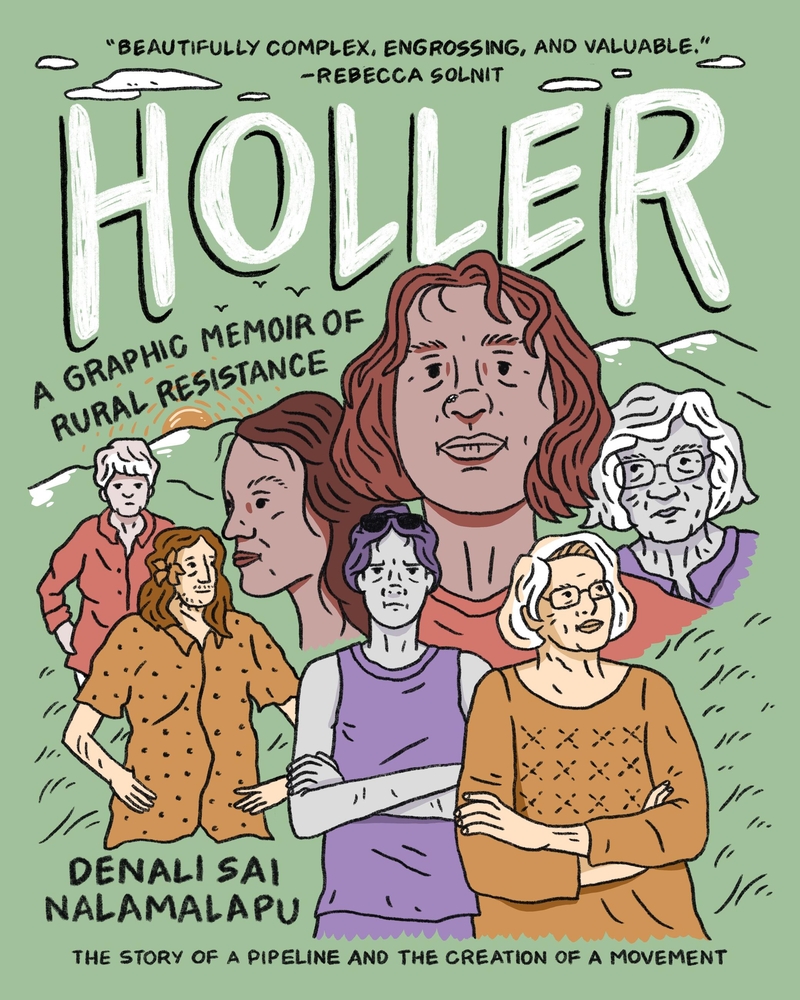

2. Holler: A Graphic Memoir of Rural Resistance

By Denali Sai Nalamalapu

An “important piece of activist art”, this beautiful graphic memoir tells the story of six hopeful activists in Appalachia who had the courage to resist against a threat to their community (Margaret Killjoy).

Drawing from original interviews with the author, Holler is an illustrated look at six inspiring changemakers. Denali Nalamalapu, a climate organizer in their own right, introduces readers to the ordinary people who became resisters of the Mountain Valley Pipeline, a project that spans approximately 300 miles from northwestern West Virginia to southern Virginia—a teacher, a single mother, a nurse, an organizer, a photographer, and a seed keeper.

In West Virginia, Becky Crabtree, grandmother of five, chains herself to her 1970s Ford Pinto to stop construction from destroying her farm. Farther south, in Virginia, young organizer Michael James-Deramo organizes mutual aid to support community members showing up to protest the pipeline expansion. These (and more) are the stories of everyday resistance that show what difference we can make when we stand up for what we love, and stand together in community. When the world tells these resisters to sit down and back off, they refuse to give up.

More than anything, Holler is an invitation to readers everywhere searching for their own path to activism: sending the message that no matter how small your action is, it’s impactful. The story of the Mountain Valley Pipeline is one we can all relate to, as each and every one of our communities faces the increasing threats of the climate crisis, and the corporations that benefit from the destruction of our natural resources. Holler is a moving and deeply accessible–and beautifully visual–story about change, hope, and humanity.

Review:

★★★★★

I’ve lived in the Shenandoah Valley my entire life, beside the beautiful Blue Ridge Mountains, and it’s so inspiring to hear from voices in my nearby community that I consider neighbors to be working towards social and environmental justice. All the work interconnects. This graphic memoir was beautifully illustrated, introducing 6 activists working against the MVP (7 including the author). An encouraging call to action.

3. Vespertine

By Margaret Rogerson

From the New York Times bestselling author of Sorcery of Thorns and An Enchantment of Ravens comes a thrilling, “dark coming-of-age adventure” (Culturess) about a teen girl with mythic abilities who must defend her world against restless spirits of the dead.

The spirits of the dead do not rest.

Artemisia is training to be a Gray Sister, a nun who cleanses the bodies of the deceased so that their souls can pass on; otherwise, they will rise as ravenous, hungry spirits. She would rather deal with the dead than the living, who whisper about her scarred hands and troubled past.

When her convent is attacked by possessed soldiers, Artemisia defends it by awakening an ancient spirit bound to a saint’s relic. It is a revenant, a malevolent being whose extraordinary power almost consumes her—but death has come, and only a vespertine, a priestess trained to wield a high relic, has any chance of stopping it. With all knowledge of vespertines lost to time, Artemisia turns to the last remaining expert for help: the revenant itself.

As she unravels a sinister mystery of saints, secrets, and dark magic, Artemisia discovers that facing this hidden evil might require her to betray everything she believes—if the revenant doesn’t betray her first.

Review:

★★★★

Margaret Rogerson is one of my favorite authors, after first reading and loving An Enchantment of Ravens. I loved this unique book as well, and it had so many themes and messages that I tend to gravitate to—along with spirits, possessions, nuns, an evil priest? Immediate yes. I rooted and related to our misunderstood main character from the beginning.

Me, the goat, the revenant, we weren’t very different from each other in the end. Perhaps deep down inside everyone was just a scared animal afraid of getting hurt, and that explained every confusing and mean and terrible thing we did.

Perhaps the decisions that shaped the course of history weren’t made in scenes worthy of stories or tapestries, but in ordinary places like these, driven by desperation and doubt.

Not quite five stars, as I felt the world building and pacing were confusing and/or lacking at times. Yet I loved this book and expect to reread it at some point.

P. S. Please someone tell me that this is going to be a series instead of a standalone!!

4. The Staircase in the Woods

By Chuck Wendig

A group of friends investigates the mystery of a strange staircase in the woods in this mesmerizing horror novel from the New York Times bestselling author of The Book of Accidents.

Five high school friends are bonded by an oath to protect one another no matter what.

Then, on a camping trip in the middle of the forest, they find something extraordinary: a mysterious staircase to nowhere.

One friend walks up—and never comes back down. Then the staircase disappears.

Twenty years later, the staircase has reappeared. Now the group returns to find the lost boy—and what lies beyond the staircase in the woods. . . .

Review:

★★★

Bummed that I didn’t love this like I thought I would. It was okay. Mostly, I didn’t feel as connected to the characters as I hoped, despite their dissected backstories and traumas throughout. I was intrigued to read about this concept, as abandoned, lone staircases are a very real happening. Wasn’t thrilled or hooked with the execution. It wasn’t as fun or as a good of a time.

TW for SA.

5. Never Whistle at Night: An Indigenous Dark Fiction Anthology

Edited By Shane Hawk and Theodore C. Van Alst Jr.

A bold, clever, and sublimely sinister collection that dares to ask the question: “Are you ready to be un-settled?”

Featuring stories by:

Norris Black • Amber Blaeser-Wardzala • Phoenix Boudreau • Cherie Dimaline • Carson Faust • Kelli Jo Ford • Kate Hart • Shane Hawk • Brandon Hobson • Darcie Little Badger • Conley Lyons • Nick Medina • Tiffany Morris • Tommy Orange • Mona Susan Power • Marcie R. Rendon • Waubgeshig Rice • Rebecca Roanhorse • Andrea L. Rogers • Morgan Talty • D.H. Trujillo • Theodore C. Van Alst Jr. • Richard Van Camp • David Heska Wanbli Weiden • Royce K. Young Wolf • Mathilda Zeller

Many Indigenous people believe that one should never whistle at night. This belief takes many forms: for instance, Native Hawaiians believe it summons the Hukai’po, the spirits of ancient warriors, and Native Mexicans say it calls Lechuza, a witch that can transform into an owl. But what all these legends hold in common is the certainty that whistling at night can cause evil spirits to appear—and even follow you home.

These wholly original and shiver-inducing tales introduce readers to ghosts, curses, hauntings, monstrous creatures, complex family legacies, desperate deeds, and chilling acts of revenge. Introduced and contextualized by bestselling author Stephen Graham Jones, these stories are a celebration of Indigenous peoples’ survival and imagination, and a glorious reveling in all the things an ill-advised whistle might summon.

Review:

★★★.5

Loved a couple of the short stories, but there were some that were absolutely not for me. Really wish there were triggers warnings before some of the stories too (for SA, in particular). Overall, a solid collection that’s worth reading.

Let me know a political book you read recently!